- The Shortness of Life: Seneca on Busyness and the Art of Living Wide Rather Than Living Long

- Montaigne’s timeless lessons on the art of living

- Alan Watts on how to live with presence

- John Armstrong: How to Worry Less About Money

- Buddhist Economics: How to Stop Prioritizing Products Over People and Consumption Over Creativity

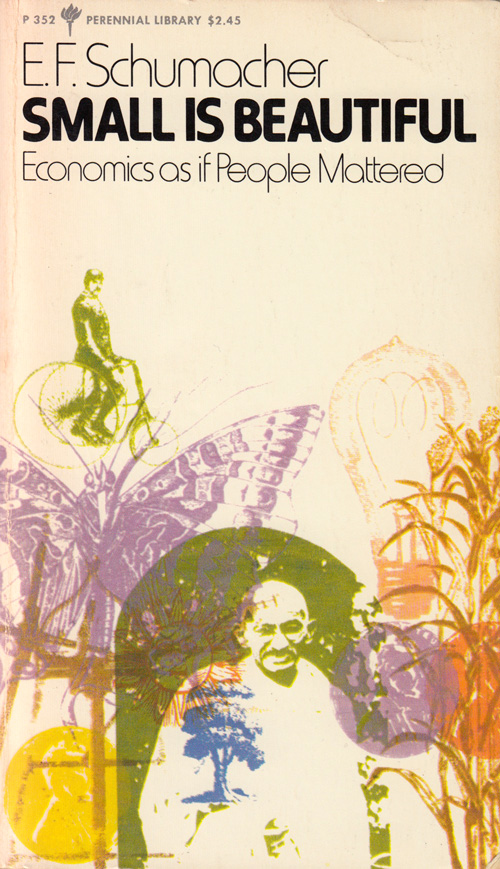

That’s precisely what the influential German-born British economist, statistician, Rhodes Scholar, and economic theorist E. F. Schumacher explores in his seminal 1973 book Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered (public library)

— a magnificent collection of essays at the intersection of economics,

ethics, and environmental awareness, which earned Schumacher the

prestigious Prix Européen de l’Essai Charles Veillon award and was

deemed by The Times Literary Supplement one of the 100 most important books published since WWII. Sharing an ideological kinship with such influential minds as Tolstoy and Gandhi, Schumacher’s is a masterwork of intelligent counterculture, applying history’s deepest, most timeless wisdom to the most pressing issues of modern life in an

effort to educate, elevate and enlighten.

One of the most compelling essays in the book, titled “Buddhist Economics,” applies spiritual principles and moral purpose to the question of wealth. Writing around the same time that Alan Watts considered the subject, Schumacher begins:

“Right Livelihood” is one of the requirements of the

Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path. It is clear, therefore, that there must

be such a thing as Buddhist economics.

[…]

Spiritual health and material well-being are not enemies: they are natural allies. #

In How to Worry Less About Money — another great installment in The School of Life’s heartening series reclaiming the traditional self-help genre as intelligent, non-self-helpy, yet immensely helpful guides to modern

living, which previously gave us Philippa Perry’s How to Stay Sane, Alain de Botton’s How to Think More About Sex, and Roman Krznaric’s How to Find Fulfilling Work — Melbourne Business School philosopher-in-residence John Armstrong guides us to arriving at our own “big views about money and its role in life,” transcending the narrow and often oppressive conceptions of our monoculture. #

0 comentários:

Enviar um comentário